Carlos E. Mijares MD highly recommend this Medical Weekly Report

www.centromedicodecaracas.com.ve

Vaccination coverage represents the percentage of persons in a target age group that received a vaccine dose. Administrative coverage is calculated by dividing the number of vaccine doses administered to those in a specified target age group by the estimated target population. Countries report administrative coverage annually to WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) through the Joint Reporting Form (JRF).* Vaccine stock management information, including availability and supply, is also reported through the JRF. Vaccination coverage surveys estimate vaccination coverage by visiting a representative sample of households with children in a specified target age group to obtain information on vaccination status. WHO and UNICEF derive national coverage estimates through an annual country-by-country review of all available data, including administrative and survey-based coverage. As new data are incorporated, revisions of past coverage estimates (2,3) and updates are published on the WHO and UNICEF websites (4,5). The WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage, on which this report is based, are revised annually and include retrospective changes in estimates if new data become available.

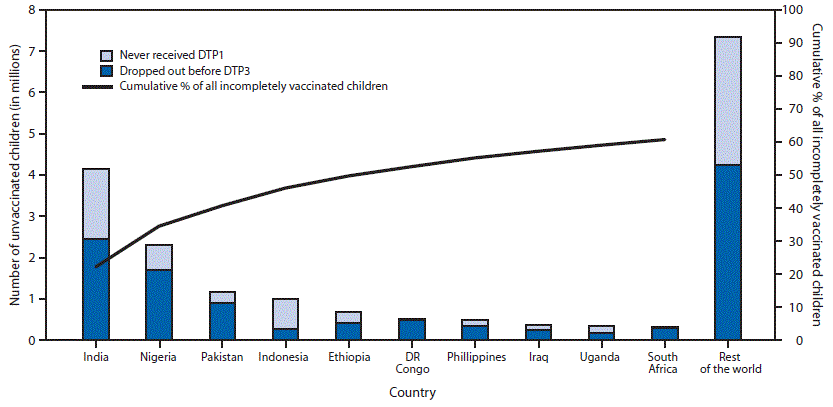

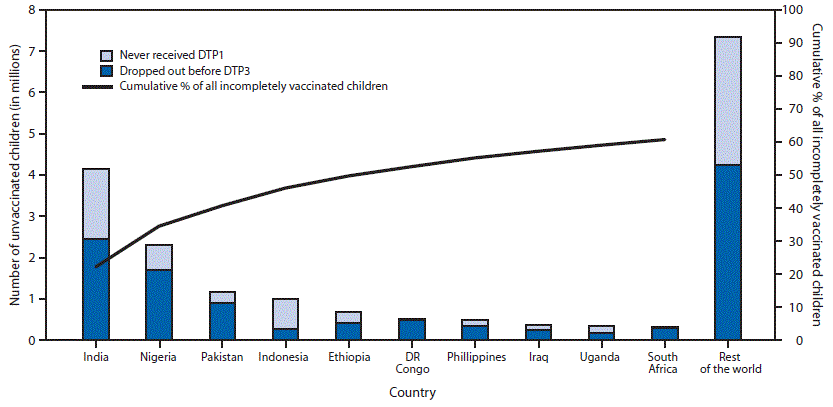

In 2014, estimated DTP3 coverage was 86% worldwide among infants aged ≤12 months, ranging from 77% in the WHO African Region to 96% in the Western Pacific Region, and representing 115.2 million vaccinated children (Table 1). Approximately 18.7 million eligible children did not complete the 3-dose series; among whom 11.5 million (61%) did not receive the 1st DTP dose, and 7.2 million (39%) started, but did not complete the 3-dose series. Estimated global coverage with BCG, polio3, and MCV1 was 91%, 86%, and 85%, respectively. During 2014, a total of 129 (66%) of 194 WHO countries achieved ≥90% national DTP3 coverage; and 57 (29%) achieved ≥80% DTP3 coverage in every district. National DTP3 coverage was 80%–89% in 30 countries, 70%–79% in 20 countries, and <70% in 15 countries. Among the 18.7 million children who did not receive 3 DTP doses during the first year of life, 9.3 million (50%) lived in five countries (India [22%], Nigeria [12%], Pakistan [6%], Indonesia [5%] and Ethiopia [4%]); 11.4 million (61%) lived in 10 countries (Figure).

Additional vaccines are increasingly being introduced into national immunization schedules. By the end of 2014, hepatitis B vaccine was included in the routine immunization schedule in 184 (95%) countries, 96 (49%) of which included a dose administered within 24 hours of birth to prevent perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission. Worldwide (including countries that have not introduced the vaccine) coverage with 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine in 2014 was 82%, and hepatitis B vaccine birth-dose coverage was 38% (Table 1). Rubella vaccine has been introduced into the routine immunization schedule in 140 (72%) countries, with an estimated coverage of 46% globally. Coverage with 3 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, which had been introduced in 192 (99%) countries† by 2014, was 56%. By 2014, rotavirus vaccine had been introduced in 74 (38%) countries, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in 117 (60%) countries. Coverage with the completed rotavirus vaccination series (2 or 3 doses, depending on the vaccine used) was 19% globally, and coverage with 3 doses of PCV was 31%. MCV2 was included in the routine immunization schedule in 154 (79%) countries, with global coverage reaching 56% in 2014. In general, coverage for all vaccines varied greatly by WHO region.

MCV2 and booster doses for DTP and poliovirus vaccine are administered after the first year of life in 163 countries. A total of 159 (82%) countries now have at least one routinely scheduled vaccination during the second year of life. The most common vaccines administered during the second year of life are MCV2 (66 countries), rubella-containing vaccine (69 countries), diphtheria-tetanus–containing boosters (107 countries), and poliovirus vaccine boosters (100 countries) (Table 2).

During 2014, a total of 50 (26%) of the 194 WHO countries reported experiencing a national level stockout, or shortage of supply, of at least one vaccine lasting at least 1 month. Overall 110 national stockout events were reported in 2014, with a mean of 2.2 events per country and a maximum of six events per country. DTP-containing vaccine shortages represented 40% of the reported stockout events, followed by BCG (25%), and MCV (14%). At the subnational level, 88% of countries with a national level stockout experienced a district level stockout. In 38 (86%) countries with a district level stockout, the primary cause identified was a national level stockout.

One key element to addressing the progress toward achieving global vaccination coverage goals is improving vaccine stock management, which is a critical component to ensuring vaccine access. The large proportion of countries experiencing district level stockouts as a result of a national level stockout provides evidence that shortage of vaccines at the national level can affect the supply chain and interrupt immunization services. Improved and timely demand forecasts to the vaccine industry are integral to help secure sufficient supplies of vaccines.

Delivering vaccination services during the second year of life provides an opportunity to fully protect children by providing booster doses, as well as vaccinating children who were missed during the first year of life. These missed opportunities leave children insufficiently protected against vaccine-preventable diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and measles into adolescence and adulthood. Establishing a routine visit for administering vaccines during the second year of life requires appropriate training of health care workers to implement new policies, ongoing support to ensure adequate reporting practices, and careful communication and social mobilization efforts to inform caregivers of the need for additional vaccines beyond infancy. Countries that already have an established health intervention visit during the second year of life might be better poised to introduce or add vaccines because of the opportunity to synergize between programs while minimizing the burden on health care workers and systems (7).

Strategies that promote vaccination beyond infancy can help create a safety net to improve coverage after service interruptions. Additionally, countries with established health care visits in the second year of life have an opportunity to work more broadly toward a life course vaccination strategy, whereby all persons are protected through routine immunization visits from infancy through adulthood, and important vaccine and health messages are reinforced at each visit.

1Global Immunization Division, CDC; 2Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC; 3Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization.

Corresponding author: Saleena Subaiya, yzv3@cdc.gov, 404-718-6596.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.

www.centromedicodecaracas.com.ve

Global Routine Vaccination Coverage, 2014

Weekly

November 13, 2015 / 64(44);1252-1255

, MD1,2; , PhD3; , MPH3; , MSc3; , MMed(Civ)3; , MD1

The year 2014 marked the 40th anniversary of the World Health

Organization's (WHO) Expanded Program on Immunization, which was

established to ensure equitable access to routine immunization services (1).

Since 1974, global coverage with the four core vaccines (Bacille

Calmette-Guérin vaccine [BCG; for protection against tuberculosis],

diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis [DTP] vaccine, poliovirus vaccine, and

measles vaccine) has increased from <5% to ≥85%, and additional

vaccines have been added to the recommended schedule. Coverage with the

3rd dose of DTP vaccine (DTP3) by age 12 months is an indicator of

immunization program performance because it reflects completion of the

basic infant immunization schedule; coverage with other vaccines,

including the 3rd dose of poliovirus vaccine (polio3); the 1st dose of

measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) is also assessed. Estimated global

DTP3 coverage has remained at 84%–86% since 2009, with estimated 2014

coverage at 86%. Estimated global coverage for the 2nd routine dose of

measles-containing vaccine (MCV2) was 38% by age 24 months and 56% when

older age groups were included, similar to levels reported in 2013 (36%

and 55%, respectively). To reach and sustain high immunization coverage

in all countries, adequate vaccine stock management and additional

opportunities for immunization, such as through routine visits in the

second year of life, are integral components to strengthening

immunization programs and reducing morbidity and mortality from vaccine

preventable diseases.Vaccination coverage represents the percentage of persons in a target age group that received a vaccine dose. Administrative coverage is calculated by dividing the number of vaccine doses administered to those in a specified target age group by the estimated target population. Countries report administrative coverage annually to WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) through the Joint Reporting Form (JRF).* Vaccine stock management information, including availability and supply, is also reported through the JRF. Vaccination coverage surveys estimate vaccination coverage by visiting a representative sample of households with children in a specified target age group to obtain information on vaccination status. WHO and UNICEF derive national coverage estimates through an annual country-by-country review of all available data, including administrative and survey-based coverage. As new data are incorporated, revisions of past coverage estimates (2,3) and updates are published on the WHO and UNICEF websites (4,5). The WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage, on which this report is based, are revised annually and include retrospective changes in estimates if new data become available.

In 2014, estimated DTP3 coverage was 86% worldwide among infants aged ≤12 months, ranging from 77% in the WHO African Region to 96% in the Western Pacific Region, and representing 115.2 million vaccinated children (Table 1). Approximately 18.7 million eligible children did not complete the 3-dose series; among whom 11.5 million (61%) did not receive the 1st DTP dose, and 7.2 million (39%) started, but did not complete the 3-dose series. Estimated global coverage with BCG, polio3, and MCV1 was 91%, 86%, and 85%, respectively. During 2014, a total of 129 (66%) of 194 WHO countries achieved ≥90% national DTP3 coverage; and 57 (29%) achieved ≥80% DTP3 coverage in every district. National DTP3 coverage was 80%–89% in 30 countries, 70%–79% in 20 countries, and <70% in 15 countries. Among the 18.7 million children who did not receive 3 DTP doses during the first year of life, 9.3 million (50%) lived in five countries (India [22%], Nigeria [12%], Pakistan [6%], Indonesia [5%] and Ethiopia [4%]); 11.4 million (61%) lived in 10 countries (Figure).

Additional vaccines are increasingly being introduced into national immunization schedules. By the end of 2014, hepatitis B vaccine was included in the routine immunization schedule in 184 (95%) countries, 96 (49%) of which included a dose administered within 24 hours of birth to prevent perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission. Worldwide (including countries that have not introduced the vaccine) coverage with 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine in 2014 was 82%, and hepatitis B vaccine birth-dose coverage was 38% (Table 1). Rubella vaccine has been introduced into the routine immunization schedule in 140 (72%) countries, with an estimated coverage of 46% globally. Coverage with 3 doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, which had been introduced in 192 (99%) countries† by 2014, was 56%. By 2014, rotavirus vaccine had been introduced in 74 (38%) countries, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in 117 (60%) countries. Coverage with the completed rotavirus vaccination series (2 or 3 doses, depending on the vaccine used) was 19% globally, and coverage with 3 doses of PCV was 31%. MCV2 was included in the routine immunization schedule in 154 (79%) countries, with global coverage reaching 56% in 2014. In general, coverage for all vaccines varied greatly by WHO region.

MCV2 and booster doses for DTP and poliovirus vaccine are administered after the first year of life in 163 countries. A total of 159 (82%) countries now have at least one routinely scheduled vaccination during the second year of life. The most common vaccines administered during the second year of life are MCV2 (66 countries), rubella-containing vaccine (69 countries), diphtheria-tetanus–containing boosters (107 countries), and poliovirus vaccine boosters (100 countries) (Table 2).

During 2014, a total of 50 (26%) of the 194 WHO countries reported experiencing a national level stockout, or shortage of supply, of at least one vaccine lasting at least 1 month. Overall 110 national stockout events were reported in 2014, with a mean of 2.2 events per country and a maximum of six events per country. DTP-containing vaccine shortages represented 40% of the reported stockout events, followed by BCG (25%), and MCV (14%). At the subnational level, 88% of countries with a national level stockout experienced a district level stockout. In 38 (86%) countries with a district level stockout, the primary cause identified was a national level stockout.

Discussion

The Global Vaccine Action Plan, 2011–2020 (GVAP), endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 2012, is a framework to provide more equitable access to vaccines. The plan calls on all countries to reach a target of 90% national coverage for all vaccines and 80% coverage in all districts by 2015, with sustained coverage levels for 3 years by 2020 (6). The number of children who had not received a 3rd dose of DTP vaccine reached an all-time low of 18.7 million in 2014. However, global DTP3 coverage has remained unchanged at 86% since 2013, with 65 (34%) countries having not yet met the GVAP target of 90% national coverage. In 18% of countries, national DTP3 coverage is <80%. The same six countries (India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Indonesia, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) have been home to more than half the world's population of unvaccinated children for the past 19 years. GVAP highlights the need to identify barriers to vaccine delivery and to ensure accountability through annual reporting of actions taken to improve immunization programs for countries experiencing stagnation in coverage.One key element to addressing the progress toward achieving global vaccination coverage goals is improving vaccine stock management, which is a critical component to ensuring vaccine access. The large proportion of countries experiencing district level stockouts as a result of a national level stockout provides evidence that shortage of vaccines at the national level can affect the supply chain and interrupt immunization services. Improved and timely demand forecasts to the vaccine industry are integral to help secure sufficient supplies of vaccines.

Delivering vaccination services during the second year of life provides an opportunity to fully protect children by providing booster doses, as well as vaccinating children who were missed during the first year of life. These missed opportunities leave children insufficiently protected against vaccine-preventable diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and measles into adolescence and adulthood. Establishing a routine visit for administering vaccines during the second year of life requires appropriate training of health care workers to implement new policies, ongoing support to ensure adequate reporting practices, and careful communication and social mobilization efforts to inform caregivers of the need for additional vaccines beyond infancy. Countries that already have an established health intervention visit during the second year of life might be better poised to introduce or add vaccines because of the opportunity to synergize between programs while minimizing the burden on health care workers and systems (7).

Strategies that promote vaccination beyond infancy can help create a safety net to improve coverage after service interruptions. Additionally, countries with established health care visits in the second year of life have an opportunity to work more broadly toward a life course vaccination strategy, whereby all persons are protected through routine immunization visits from infancy through adulthood, and important vaccine and health messages are reinforced at each visit.

1Global Immunization Division, CDC; 2Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC; 3Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization.

Corresponding author: Saleena Subaiya, yzv3@cdc.gov, 404-718-6596.

References

- Uwizihiwe JP, Block H. 40th anniversary of introduction of Expanded Immunization Program (EPI): a literature review of introduction of new vaccines for routine childhood immunization in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J Vaccines Vaccin 2015;1:00004.

- Burton A, Monasch R, Lautenbach B, et al. WHO and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: methods and processes. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:535–41.

- Burton A, Kowalski R, Gacic-Dobo M, Karimov R, Brown D. A formal representation of the WHO and UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage: a computational logic approach. PLoS One 2012;7:e47806.

- World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF coverage estimates. Available at http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/en

.

. - United Nations Children's Fund. Statistics by topic (child/health/immunization). Available at http://data.unicef.org/child-health/immunization.html

.

. - Global Vaccine Action Plan. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts

on Immunization. 2014 assessment report of the Global Vaccine Action

Plan. Available at http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/SAGE_DoV_GVAP_Assessment_report_2014_English.pdf?ua=1

.

. - Sodha SV, Dietz V. Strengthening routine immunization systems to improve global vaccination coverage. Br Med Bull 2015;113:5–14.

* Administrative data reported to WHO and UNICEF annually are available at http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/administrative_coverage.xls

.

.

† Includes parts of Belarus, India and Russian Federation.

Summary

What is already known on this topic?

In 1974, the World Health Organization

established the Expanded Program on Immunization to ensure that all

children have access to routinely recommended vaccines. Since then,

global coverage with vaccines to prevent tuberculosis, diphtheria,

tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, and measles has increased from <5%

to ≥85%, and additional vaccines have been added to the recommended

schedule. Coverage with the 3rd dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis

vaccine by age 12 months is an indicator of immunization program

performance.

What is added by this report?

The number of countries offering

vaccination in the second year of life is increasing. However,

substantial barriers to improving coverage still remain, including

national vaccine stockouts, or shortage of supplies.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Administering vaccines during the second

year of life is a critical opportunity to provide catch up vaccinations

and allows countries to progress toward a life course immunization

strategy. Establishing a routine visit for administering vaccines during

the second year of life requires appropriate training of health care

workers to implement new policies, ongoing support to ensure adequate

reporting practices, and careful communication and social mobilization

efforts to inform caregivers of the need for additional vaccines beyond

infancy.

FIGURE. Estimated number of

children who did not receive 3 doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis

vaccine (DTP3) during the first year of life among 10 countries with the

largest number of incompletely vaccinated children and cumulative

percentage of all incompletely vaccinated children worldwide accounted

for by these 10 countries, 2014

Abbreviations: DTP1 = 1st dose of

diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine; DTP3 = 3 doses of

diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine; DR Congo = Democratic Republic of

the Congo.

Alternate Text: The figure above is a bar

chart showing the estimated number of children who did not receive 3

doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine during the first year of

life among 10 countries with the largest number of incompletely

vaccinated children and cumulative percentage of all incompletely

vaccinated children worldwide accounted for by these 10 countries during

2014.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.

- Page last reviewed: November 13, 2015

- Page last updated: November 13, 2015

- Content source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1600 Clifton Road Atlanta, GA 30329-4027, USA

800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636) TTY: (888) 232-6348 - Contact CDC–INFO

800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636) TTY: (888) 232-6348 - Contact CDC–INFO